ISSUE #17 - English Edition

COVER STORY

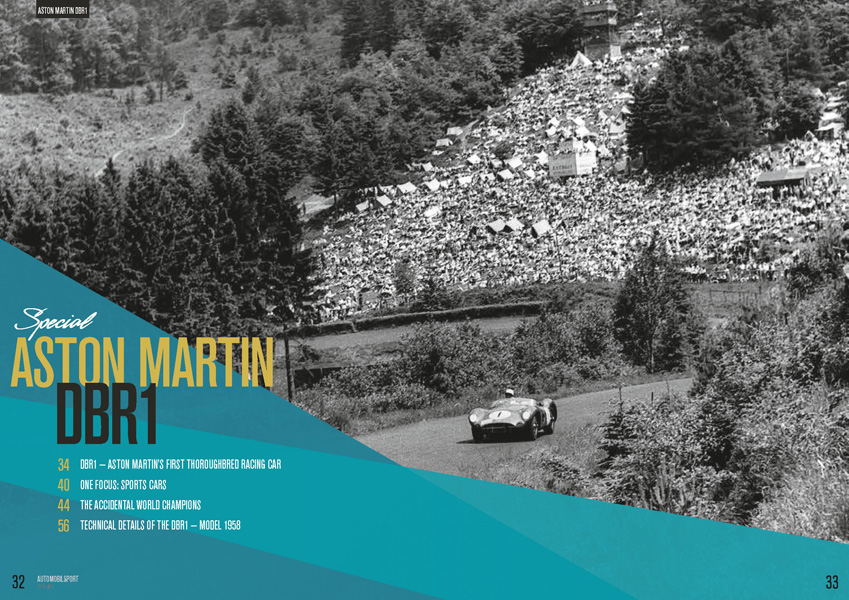

Aston Martin DBR1

DBR1 - Aston Martin’s first thoroughbred racing car

ONE FOCUS: SPORTS CARS

THE ACCIDENTAL WORLD CHAMPIONS

TECHNICAL DETAILS OF THE DBR1 — MODEL 1958

DBR1

Aston Martin’s first thoroughbred racing car

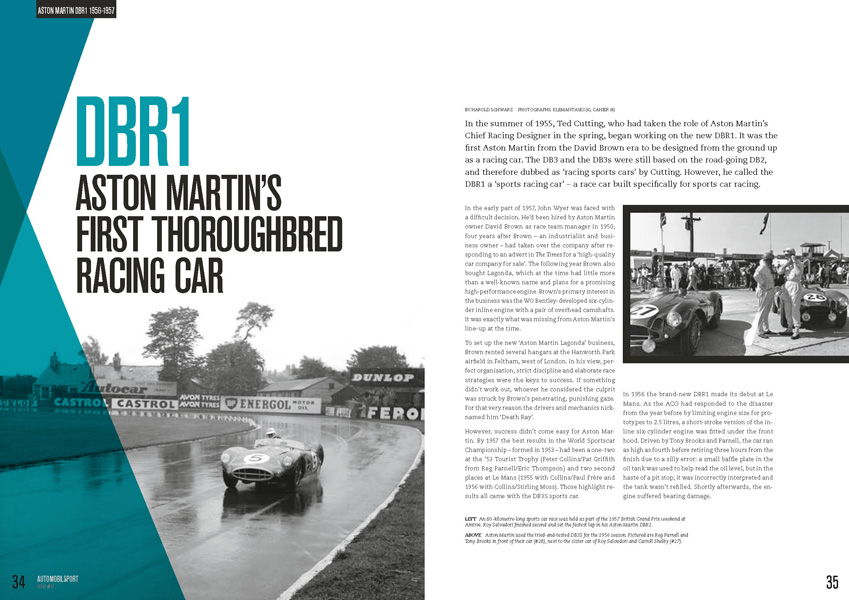

In the summer of 1955, Ted Cutting, who had taken the role of Aston Martin’s Chief Racing Designer in the spring, began working on the new DBR1. It was the first Aston Martin from the David Brown era to be designed from the ground up as a racing car. The DB3 and the DB3s were still based on the road-going DB2, and therefore dubbed as ‘racing sports cars’ by Cutting. However, he called the DBR1 a ‘sports racing car’ – a race car built specifically for sports car racing.

In the early part of 1957, John Wyer was faced with a difficult decision. He’d been hired by Aston Martin owner David Brown as race team manager in 1950, four years after Brown – an industrialist and business owner – had taken over the company after responding to an advert in The Times for a ‘high-quality car company for sale’. The following year Brown also bought Lagonda, which at the time had little more than a well-known name and plans for a promising high-performance engine. Brown’s primary interest in the business was the WO Bentley-developed six-cylinder inline engine with a pair of overhead camshafts. It was exactly what was missing from Aston Martin’s line-up at the time.

To set up the new ‘Aston Martin Lagonda’ business, Brown rented several hangars at the Hanworth Park airfield in Feltham, west of London. In his view, perfect organisation, strict discipline and elaborate race strategies were the keys to success. If something didn’t work out, whoever he considered the culprit was struck by Brown’s penetrating, punishing gaze. For that very reason the drivers and mechanics nicknamed him ‘Death Ray’.

However, success didn’t come easy for Aston Martin. By 1957 the best results in the World Sportscar Championship – formed in 1953 – had been a one-two at the ’53 Tourist Trophy (Peter Collins/Pat Griffith from Reg Parnell/Eric Thompson) and two second places at Le Mans (1955 with Collins/Paul Frère and 1956 with Collins/Stirling Moss). Those highlight results all came with the DB3S sports car…

by Harold Schwarz

Photographs: Klemantaski, Cahier

The Accidental World Champions

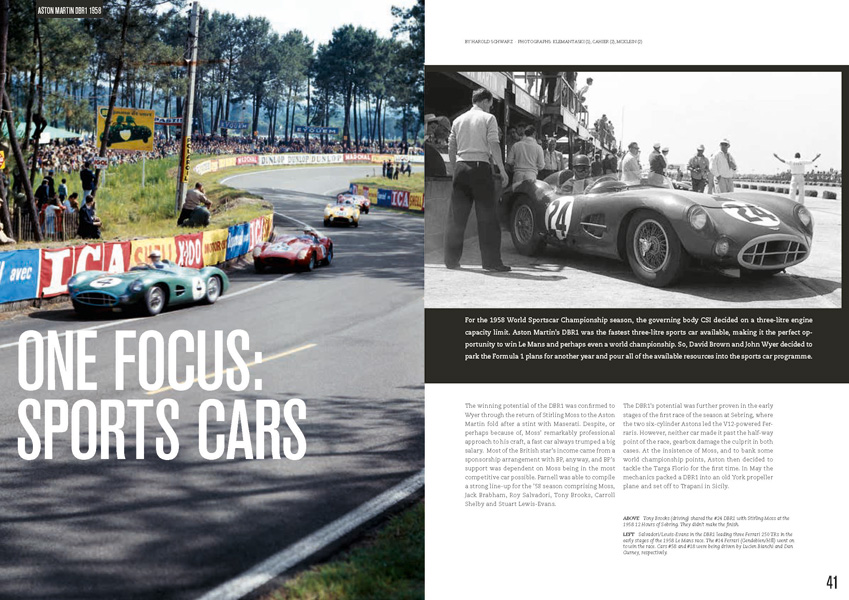

When the plans for the previous season failed, Aston Martin completely changed its strategy for 1959. David Brown, John Wyer and Reg Parnell opted to prioritise Formula 1 and limit the sports car programme to the 24 Hours of Le Mans.

The Aston Martin strategists felt it was the right way to go, working on the assumption that the DBR1 was still the fastest three-litre car. Any sports car races outside of Le Mans were considered nothing more than a distraction.

Aston Martin had been trying to win at Le Mans for nine years, and failed each and every time. The biggest culprit was reliability, leading Wyer to conclude that perhaps they’d tried to bite off more than they could chew in the past. The new philosophy was that Le Mans success would hinge on reliability and stability. So, rather than try and make the DBR1 quicker, all efforts went into bullet-proofing the car.

But even the best-laid plans can quickly change. For Aston Martin it started with a plea from the 12 Hours of Sebring organisers Alex Ullmann and Reggie Smith to take part in their race. They even offered to pay all of the travel expenses for the long journey. Once motorsport boss Parnell joined the chorus of pleas to head to Florida, Wyer relented – something he later admitted was a mistake. There was never enough time to properly prepare the car for Salvadori and Shelby. Salvadori led the early stages of the races, but soon lost time with a slipping clutch. It turned out the culprit was an overactive oil pump leading to the mechanics overfilling the engine, with the excess oil making its way into the clutch housing. Carroll Shelby then broke the gear lever off and parked the car 32 laps in…

by Harold Schwarz

Photographs: Cahier, McKlein, Klemantaski, LAT

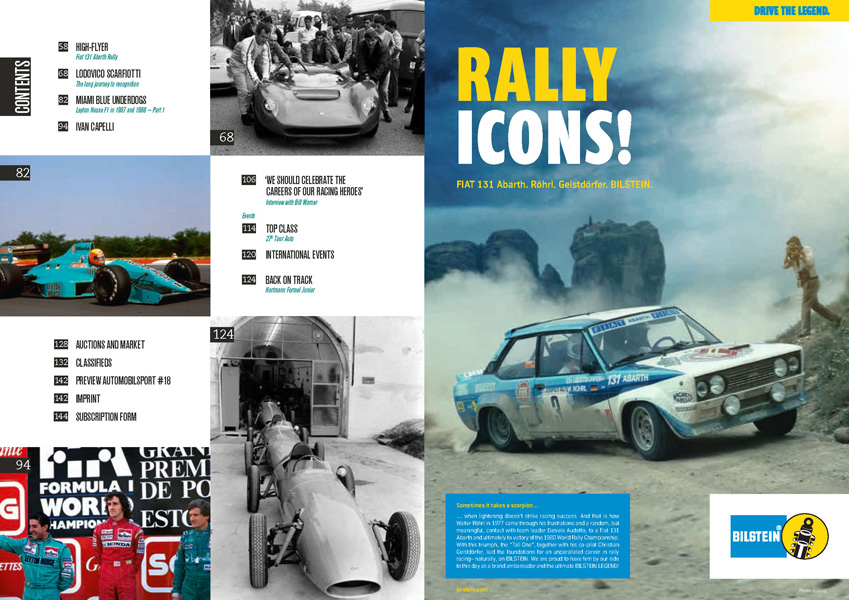

Fiat 131 Abarth Rally:

High-Flyer

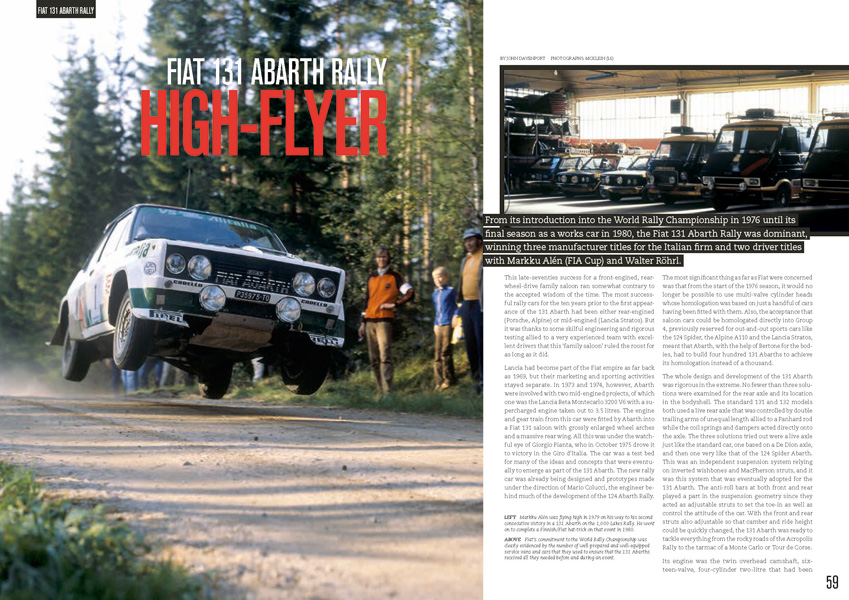

From its introduction into the World Rally Championship in 1976 until its final season as a works car in 1980, the Fiat 131 Abarth Rally was dominant,winning three manufacturer titles for the Italian firm and two driver titles with Markku Alén (FIA Cup) and Walter Röhrl.

This late-seventies success for a front-engined, rear-wheel-drive family saloon ran somewhat contrary to the accepted wisdom of the time. The most successful rally cars for the ten years prior to the first appearance of the 131 Abarth had been either rear-engined (Porsche, Alpine) or mid-engined (Lancia Stratos). But it was thanks to some skilful engineering and rigorous testing allied to a very experienced team with excellent drivers that this ‘family saloon’ruled the roost for as long as it did.

Lancia had become part of the Fiat empire as far back as 1969,but their marketing and sporting activities stayed separate. In1973 and 1974, however,Abarth were involved with two mid-engined projects,of which one was the Lancia Beta Montecarlo 3200 V6 with a supercharged engine taken out to 3.5litres. The engine and geartrain from this car were fitted by Abarth into a Fiat 131 saloon with grossly enlarged wheel arches and a massive rear wing. All this was under the watchful eye of Giorgio Pianta,who in October 1975 drove it to victory in the Giro d’Italia. The car was a test bed for many of the ideas and concepts that were eventually to emerge as part of the 131 Abarth. The new rally car was already being designed and prototypes made under the direction of Mario Colucci, the engineer behind much of the development of the 124 Abarth Rally.

The most significant thing as far asFiat were concerned was that from the start of the 1976 season, it would no longer be possible to use multi-valve cylinder heads whose homologation was based on just a handful of cars having been fitted with them. Also, the acceptance that saloon cars could be homologated directly into Group 4, previously reserved for out-and-out sports cars like the 124 Spider, the Alpine A110 and the Lancia Stratos, meant that Abarth, with the help of Bertone for the bodies, had to build four hundred 131 Abarths to achieve its homologation instead of a thousand…

by John Davenport

Photographs: McKlein

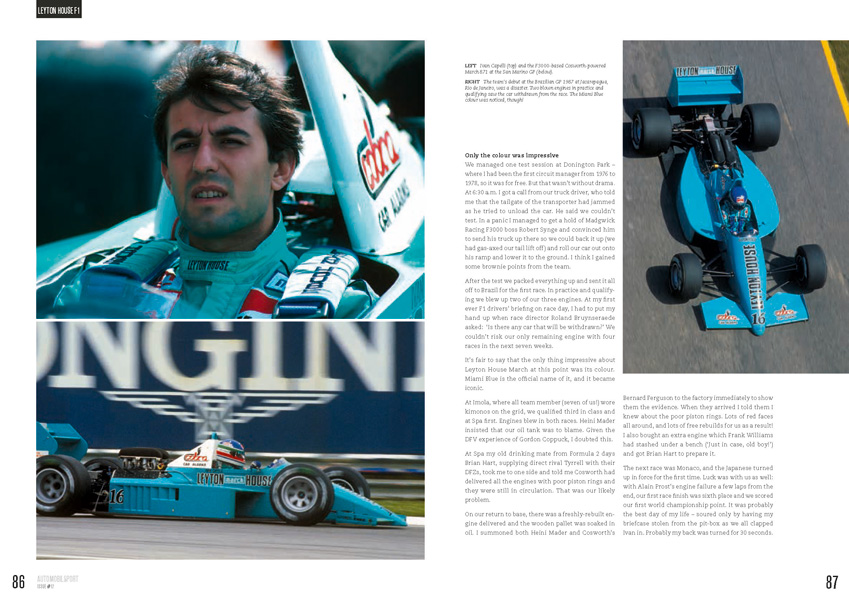

Miami Blue Underdogs

Leyton House F1 in 1987 and 1988

After a hiatus of four years, March returned to Formula 1 in 1987 with Japanese sponsorship money and a distinctive ‘Miami Blue’ livery. The budget was meagre, the staff was small, the drivers Ivan Capelli and Mauricio Gugelmin were F1 rookies – less than ideal circumstances to say the least. Nevertheless, the team took sixth place in the 1988 constructors’ championship, ahead of Williams who had won the title the year before. Exclusively for AUTOMOBILSPORT, then-team manager Ian Phillips recounts how it all happened.

The origins of the Leyton House F1 team go back to themiddle of 1986. Leyton Housewas the fashion hobby of Korean-born, Tokyo-based property magnate Akira Akagi. His brand was sponsoring a host of cars racing in the Japanese domestic championships. Their lead driver Akira Hagiwara was killed testing their Mercedes 190 E at the Sugo circuit in April. Although Formula 3000replaced Formula 2in Europe in 1985, F2 was in its final Japanese season and Leyton House had entered a pair of March-Yamahas.

I was working for Marlboro in Japan that year,principally looking after Mike Thackwell at Nova Racing. As I was also covering the European F3000 Championship and writing Autosport’s news pages,it was a busy year. No less than nineteentrips to Japan,and you couldn’t go direct from the UK until late that year. I spent many hours at Anchorage Airport in Alaska which was the standard stopover point where, more often than not, it snowed and we could be delayed by many hours.

Ivan Capelli, 1984 European Formula 3champion, was a leading force in the second year of the F3000 championship (which he eventually won) for Cesare Gariboldi’s single-car Genoa Racing team. Bridgestone’s boss Hiroshi Yasukawa initially approached Capelli to join the Leyton House F2 team and was able to offer some much-needed sponsorship to Gariboldi. Marlboro were also supportive,so I nowhad two people to look after in Japan…

by Ian Phillips

Photographs: GRANDPRIXIMAGES/John Townsend, Sutton, Sammlung Ian Phillips, GRANDPRIXPHOTO/Peter Nygaard, Kräling

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

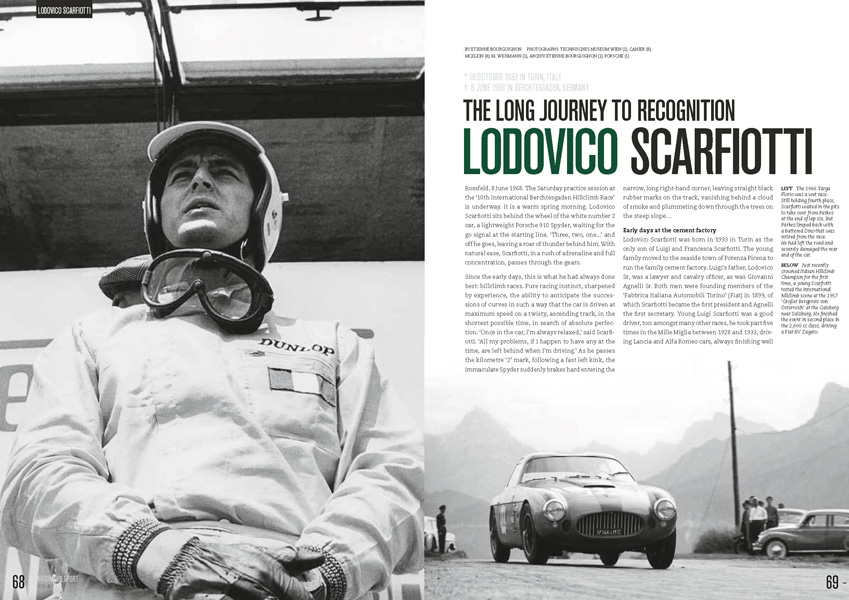

- Etienne Bourguignon on Lodovico Scarfiotti

- Eckhard Schimpf on the classic Trento-Bondone hillclimb

- Ian Phillips on Ivan Capelli

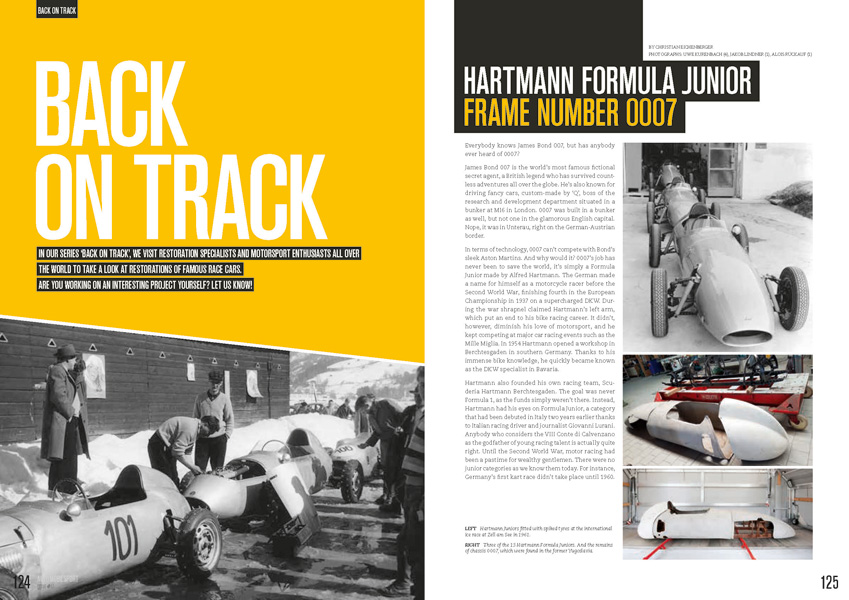

- Back on Track Hartmann Formel Junior

- and many more!

This product was added to our catalog on Wednesday 20 March, 2019.