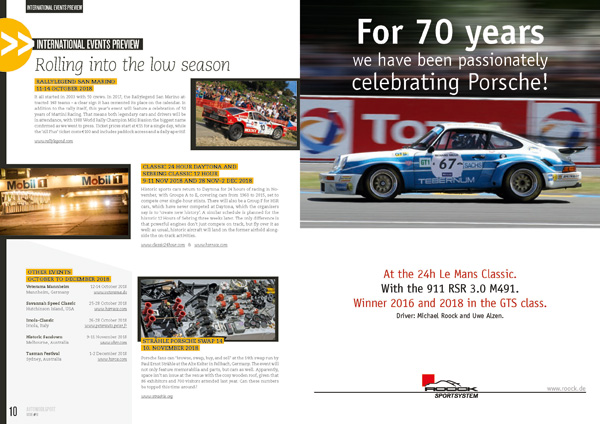

ISSUE #18 - - English Edition

COVER STORY

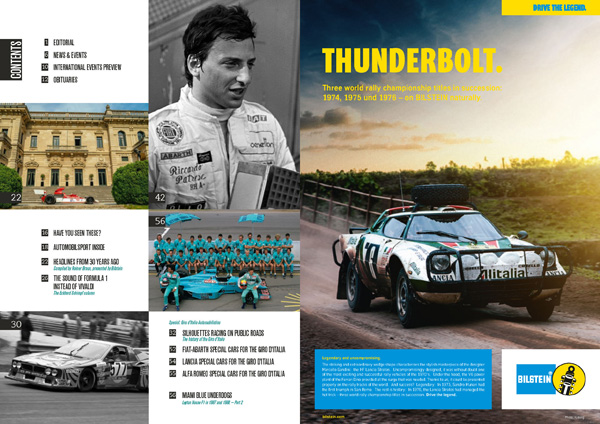

Giro d'Italia Automobilistico

SILHOUETTES RACING ON PUBLIC ROADS — Giro d’Italia Automobilistico

“I ENJOYED THE RALLY EXPERIENCE IMMENSELY!”

— Interview with Riccardo Patrese

“A 600 HP MONSTER ON THE ROAD? I COULDN’T SAY NO!”

— Interview with Emilio Radelli

FIAT-ABARTH, LANCIA AND ALFA ROMEO SPECIAL CARS FOR THE GIRO D'ITALIA

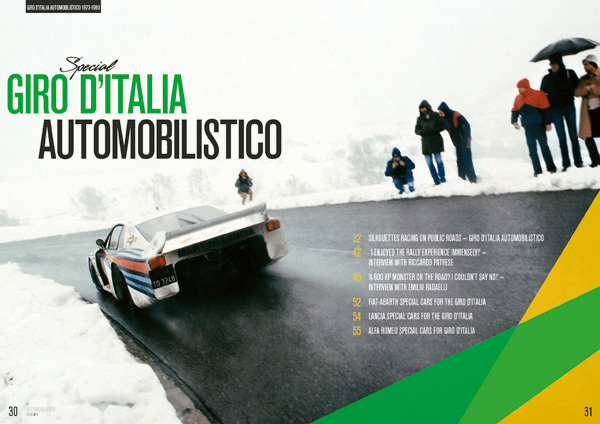

Silhouettes racing on public roads:

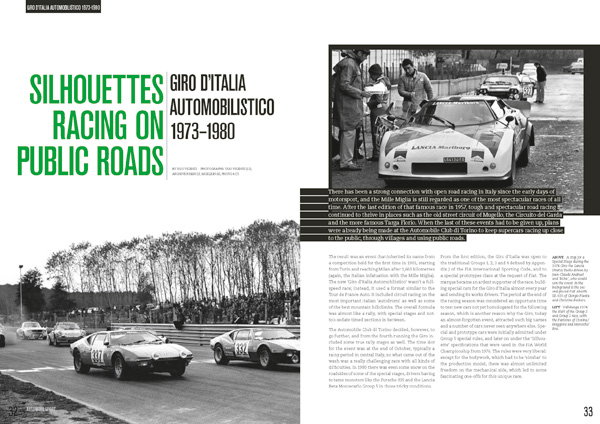

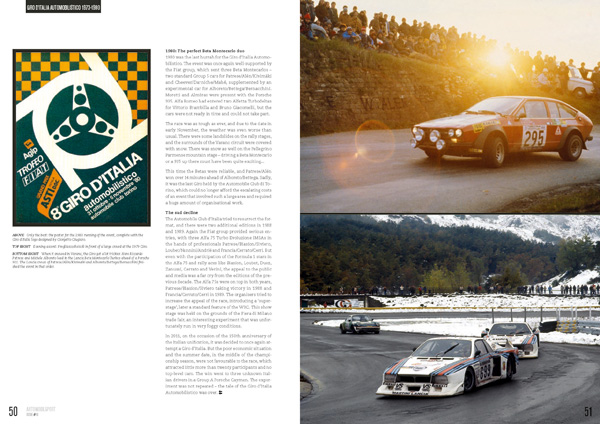

Giro d’Italia Automobilistico 1973-1980

There has been a strong connection with open road racing in Italy since the early days of motorsport, and the Mille Miglia is still regarded as one of the most spectacular races of all time. After the last edition of that famous race in 1957, tough and spectacular road racing continued to thrive in places such as the old street circuit of Mugello, the Circuito del Garda and the more famous Targa Florio. When the last of these events had to be given up, plans were already being made at the Automobile Club di Torino to keep supercars racing up close to the public, through villages and using public roads.

The result was an event that inherited its name from a competition held for the first time in 1901, starting from Turin and reaching Milan after 1,660 kilometres (again, the Italian infatuation with the Mille Miglia). The new ‘Girod’Italia Automobilistico’ wasn’t a full-speed race; instead, it used a format similar to the Tour de France Auto. It included circuit racing on the most important Italian ‘autodromi’ as well as some of the best mountain hillclimbs. The overall formula was almost like a rally, with special stages and not-too-sedate timed sections in between.

The Automobile Club di Torino decided, however, to go further, and from the fourth running the Giro included some true rally stages as well. The time slot for the event was at the end of October, typically a rainy period in central Italy, so what came out of the wash was a really challenging race with all kinds of difficulties. In 1980 there was even some snow on the roadsides of some of the special stages, drivers having to tame monsters like the Porsche 935 and the Lancia Beta Montecarlo Group 5 in those tricky conditions.

From the first edition, the Giro d’Italia was open to the traditional Groups 1, 2, 3 and 4 defined by Appendix J of the FIA International Sporting Code, and to a special prototypes class at there quest of Fiat. The marque became an ardent supporter of the race, building special cars for the Giro d’Italia almost every year and sending its works drivers. The period at the end of the racing season was considered an opportune time to test new cars not yet homologated for the following season, which is another reason why the Giro, today an almost-forgotten event, attracted such big names and a number of cars never seen anywhere else. Special and prototype cars were initially admitted under Group 5 special rules, and later on under the ‘Silhouette’ specifications that were used in the FIA World Championship from 1976. The rules were very liberal: except for the bodywork, which had to be ‘similar’ to the production model, there was almost unlimited freedom on the mechanical side, which led to some fascinating one-offs for this unique race…

by Ugo Vicenzi

Photographs: Ugo Vicenzi, Archive Riseri, McKlein, Photo 4

Miami Blue Underdogs – Part 2

Leyton House F1 in 1987 and 1988

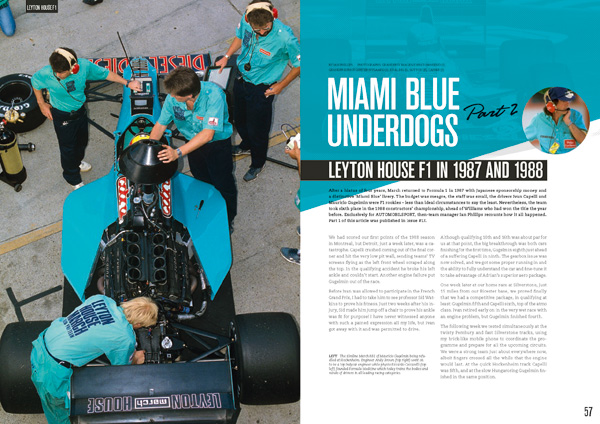

After a hiatus of four years, March returned to Formula 1 in 1987 with Japanese sponsorship money and a distinctive ‘Miami Blue’ livery. The budget was meagre, the staff was small, the drivers Ivan Capelli and Mauricio Gugelmin were F1 rookies – less than ideal circumstances to say the least. Nevertheless, the team took sixth place in the 1988 constructors’ championship, ahead of Williams who had won the title the year before. Exclusively for AUTOMOBILSPORT, then-team manager Ian Phillips recounts how it all happened. Part 1 of this article was published in Issue #17.

We had scored our first points of the 1988 season in Montreal, but Detroit, just a week later, was a catastrophe. Capelli crashed coming out of the final corner and hit the very low pit wall, sending teams’ TV screens flying as the left front wheel scraped along the top. In the qualifying accident he broke his left ankle and couldn’t start. Another engine failure put Gugelmin out of the race.

Before Ivan was allowed to participate in the French Grand Prix, I had to take him to see professor Sid Watkins to prove his fitness. Just two weeks after his injury, Sid made him jump off a chair to prove his ankle was fit for purpose! I have never witnessed anyone with such a pained expression all my life, but Ivan got away with it and was permitted to drive.

Although qualifying 10th and 16th was about par for us at that point, the big breakthrough was both cars finishing for the first time, Gugelmin eighth just ahead of a suffering Capelli in ninth. The gearbox issue was now solved, and we got some proper running in and the ability to fully understand the car and fine-tune it to take advantage of Adrian’s superior aero package.

One week later at our home race at Silverstone, just 15 miles from our Bicester base, we proved finally that we had a competitive package, in qualifying at least: Gugelmin fifth and Capelli sixth, top of the atmo class. Ivan retired early on in the very wet race with an engine problem, but Gugelmin finished fourth…

by Ian Phillips

Photographs: Grandprix Images/John Townsend, Grandprixphoto/Peter Nygaard, Kräling, Sutton, Cahier

“We needed to produce a highly efficient aero package”

Adrian Newey on Leyton House F1 and his first Formula 1 car

Adrian Newey was already a legend at March Engineering when he joined the fledgling Leyton House March F1 team in late July 1987. He’d designed championship-winning IMSA sports cars and dominant, all-conquering Indycars for the Bicester-based company all before he was 25 years old. March boss Robin Herd told him in 1986 that he hoped to get back into Formula 1. That materialised in 1987 and Adrian rejoined the company. His March 881 was to change the face of F1 design forever. For AUTOMOBILSPORT, Newey recounts how he managed to do it and what inspired his work.

Negotiations with Robin dragged on a bit, but by late July, early August I was able to start work on a clean-sheet-of-paper, genuine Formula 1 car to replace the F3000-based car the team had been using. At the same time, I had to fulfil my race engineering commitments with Mario Andretti in America which went right through to November. The transatlantic flights were exhausting, but gave me a lot of thinking time. What’s great about a plane is that there’s nothing else to do and no time pressure. It’s pure thinking time and time to sketch it down.

The design team was tiny. I was the aerodynamicist, assisted by excellent design engineer Tim Holloway, who I worked well with at March, plus the experienced Gordon Coppuck and Ray Stokoe. We also had Nick Wirth, fresh from university, who helped with the model making and wind tunnel testing. I felt at home there. It was a good little team; great morale, no politics and an environment where I found it easy to be creative. The complete opposite to my brief Beatrice Haas F1 experience, which had been so bad I couldn’t come up with any ideas.

We used the Southampton University tunnel where we did five-day sessions about once a month, with just myself, Nick and a model maker. It’s unbelievable what we achieved compared to today’s standards. Basically, what I did was take my knowledge of how we’d developed the Indycar aero and mechanical package and reapply it to F1. I think the turbo F1 cars at that time had become really clumsy. They were aerodynamically backwards and not particularly well-packaged. To go quicker, teams just turned up the boost…

by Ian Phillips/Adrian Newey

Photographs: Cahier, Sutton, Motorsportimages, McKlein, Kräling

Only Flying is More Exciting

Opel GT Conrero Gr. 4

When Opel introduced the GT exactly 50 years ago, the company was already successfully competing in various European races with models like the Rallye Kadett, the Rekord Sprint and the Commodore GS. The GT was also designed with motorsport in mind, and to showcase Opel’s changing image with its sheer looks. ‘Only flying is more exciting’ was the advertising slogan for the Opel GT. The Grand Tourisme coupé didn’t do battle with the touring cars, though. Instead, it was the perennial outsider among the Porsche 911 and 914/6, the lightweight Renault Alpine A110, the Lancias, Alfas and other two-litre cars. The GT entered the racing and rallying competition during the late 1960s, a spectacular era of motorsport. One of the professional tuners who helped extract every last bit of performance from the car was Virgilio Conrero. The Italian ‘magician’ would have turned 100 this year.

Throughout the development of the GT with its various evolutionary stages, one question more than any other divided opinions at Opel in Rüsselsheim: where the engine should be positioned in the car. The GT was based on the Kadett platform, and given that it had the same front axle, it was logical for the engineers to place the engine right there. That would have been the simplest and, above all, most cost-effective solution, but the resulting weight distribution and handling were less than optimal. Moreover, having the engine at the front was a bad fit with the proposed design of the car, which envisioned a low front hood.

The American Bob Lutz, a young Marketing and Sales manager at Opel, proposed putting the engine behind the axle. After quite a bit of discussion, the decision was made to compare both designs at a test session. Hans Herrmann and Eberhard Mahle were enlisted to do some laps at the Nürburgring in July 1966. The cars used were the experimental GT which had been on display at the 1965 International Motor Show Germany and the prototype from Technical Management.

Lutz later recalled being very impressed by how the test session went. Both experimental GTs had identical 1.9-litre engines. The test was ‘blind’, meaning that neither driver knew which car was fitted with the forward engine and which one with the centrally-mounted version. Although both GTs were good, Herrmann noticed immediately that the car with the conventional engine position was lazier to react, showed more understeer and had a greater tendency towards lateral movement. The GT with the centrally-mounted engine, by contrast, had a more pleasant, neutral handling and achieved better lap times. It felt more like a sports car: quick, easily manoeuvrable, and well-balanced. Eberhard Mahle was more reserved in his judgement, but Hans Herrmann unequivocally supported the centrally-mounted version…

by Maurice van Sevecotte/Stefan Müller

Photographs: Kräling, Collection Maurice van Sevecotte

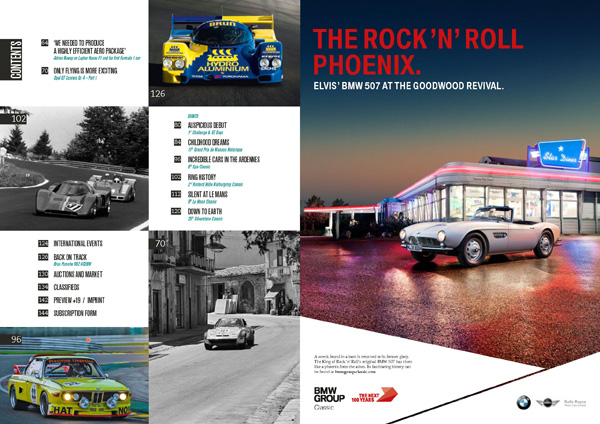

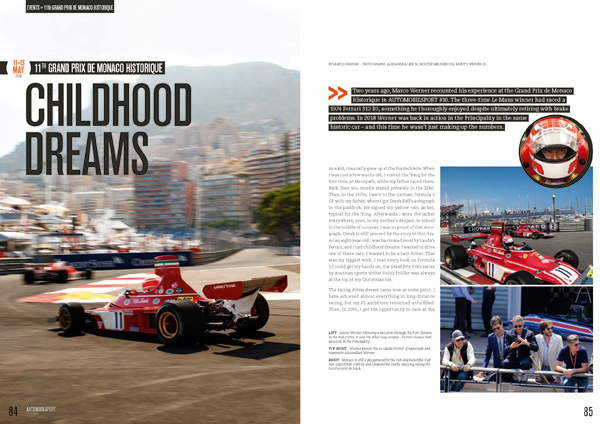

Childhood Dreams

Two years ago, Marco Werner recounted his experience at the Grand Prix de Monaco Historique in AUTOMOBILSPORT #10. The three-time Le Mans winner had raced a 1974 Ferrari 312 B3, something he thoroughly enjoyed despite ultimately retiring with brake problems. In 2018 Werner was back in action in the Principality in the same historic car – and this time he wasn’t just making up the numbers.

As a kid, I basically grew up at the Nordschleife. When I was just a few weeks old, I visited the ’Ring for the first time, at Meuspath, while my father raced there. Back then you mostly stayed privately in the Eifel. Then, in the 1970s, I went to the German Formula 1 GP with my father, where I got Derek Bell’s autograph in the paddock. He signed my yellow rain jacket, typical for the ’Ring. Afterwards I wore the jacket everywhere, even, to my mother’s despair, to school in the middle of summer. I was so proud of that autograph. Derek is still amused by the story to this day. As an eight-year-old I was fascinated most by Lauda’s Ferrari, and I had childhood dreams. I wanted to drive one of these cars. I wanted to be a race driver. That was my biggest wish. I read every book on Formula 1 I could get my hands on, the Grand Prix Storyseries by Austrian sports writer Heinz Prüller was always at the top of my Christmas list.

The racing driver dream came true at some point. I have achieved almost everything in long-distance racing, but my F1 ambitions remained unfulfilled. Then, in 2016, I got the opportunity to race at the Grand Prix Historique in Monaco. The car: a 1974 Lauda Ferrari. My greatest childhood dream, with a little delay, was coming true after all. The owner had only recently acquired the car, which had not been used in a long time except for a few demo runs. I didn’t make it to testing, which meant I was supposed to drive the car for the very first time in Monaco. Then, the dream was almost over before it had really begun: it turned out that the 40-year-old engine was disintegrating. We were able to make the start and do a couple of laps, but in the race the brake pedal broke as well and I had to retire prematurely.

Everyone agreed that we needed to return to Monaco in 2018. At Methusalem in Cologne, the Ferrari and Maserati specialists, the Ferrari 312 B3 was overhauled. Mario Linke and his team did the seemingly impossible and breathed new life into the car. Whereas I had been limited to 8,000 revs two years ago, I would now have the full 12,500 at my disposal! The hard work meant I had the same level of performance experienced by Lauda himself. After all, a 12-cylinder engine loves to rev…

by Marco Werner

Photographs: Alexandra Lier, Wouter Melissen, Moritz Werner

ALSO IN THIS ISSUE

- Eckhard Schimpf about Villa d'Este

- Brian Redman on the Chevron B16

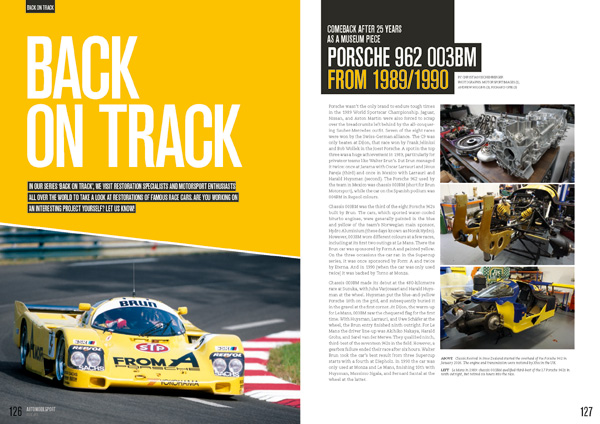

- Back on Track Brun-Porsche 962-003 BM

- and many more!

This product was added to our catalog on Wednesday 20 March, 2019.